(Content Note: suicide and infanticide are mentioned in this post)

Who am I?

I am a veterinarian.

I had my first baby at 32.

I developed postnatal psychosis after the birth of that baby.

I had no history of mental illness before that.

I have a perfectionist personality.

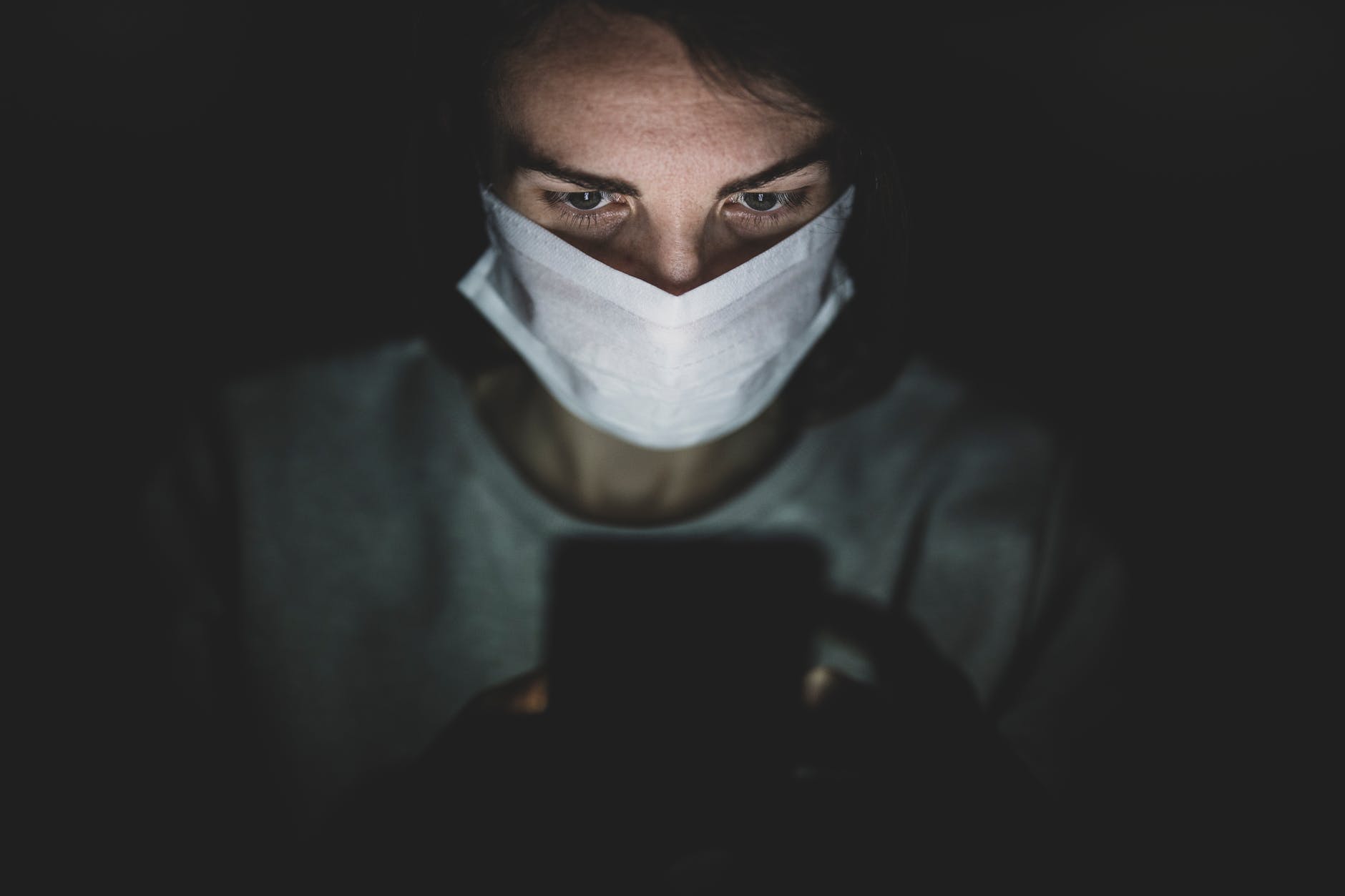

This is me.

But given this information, you could mistake me for Melissa Arbuckle.

If you’ve read even just the headlines this week, you will know Melissa’s baby Lily died in horrific circumstances, as a direct result of Melissa’s undiagnosed postnatal psychosis and depression.

Melissa’s story is an important one. But I have yet to read a story by a journalist who gets the narrative of postnatal psychosis (or any form of psychosis) right. Journalism around psychosis, even decent journalism, focusses on the sensational.

But despite the inevitable sensationalism, in this case the journalists got one thing right. They investigated the lead up to this horror story. And that shows us the number of times this horrific outcome could have been prevented.

Melissa’s baby was born in April 2021.

The Age reports ‘Maternal health notes showed that as early as May 19 the new mother revealed she was having difficulty coping and became teary, later telling a lactation consultant she felt ‘out of control’.

According to News.com ‘Victoria’s Supreme Court heard that in the weeks leading up to Lily’s death, Ms Arbuckle had been ‘really down’ and she believed she injured her baby after rocking her bassinet too vigorously.’

She hadn’t injured her baby at that point, but her thoughts (believing she had injured her baby) were delusional, for weeks before her daughter’s death.

The Age also reports ‘The night before the incident, Arbuckle told her husband she was having suicidal thoughts, but assured him she could never go through with it.’

Lily died and Melissa nearly died after being struck by a train on the following day, July 11 2021.

Melissa was diagnosed with postpartum depression and psychosis the day after her daughter died.

When I think of all the points on this timeline that Melissa’s and Lily’s odds could have been dramatically improved, anger steals my breath.

Regarding the Maternal health notes made in May 2021:

‘Maternal health notes’ imply a nurse or midwife assessed Melissa at some point and, aside from making some notes about her difficulty coping and being teary, did nothing.

Midwives and nurses need to be taught: The baby blues and mild anxiety are not always the cause of a teary mother who is having difficulty coping. They need to know when and how to refer a new mother for assessment with a psychologist, psychiatrist, a mother baby unit, or at least a GP. And they need to err on the side of caution!

I am not surprised a lactation consultant didn’t know what to do with a mother feeling out of control. Lactation consultants tend to be laser focussed on getting breast milk into babies at all costs. But again – educating lactation consultants to look far enough beyond ‘latching issues’ and ‘milk supply’ to consider referral to qualified mental health care professionals when red flags are raised, would be a good idea.

In the weeks before Lily’s death, when Melissa is described as ‘really down’ – these were the weeks that preceded the night before Lily’s death.

The night when Melissa told her husband she was having suicidal thoughts.

From my standpoint and lived experience, I struggle to give Melissa’s husband much benefit of the doubt here. I understand (based on the article in The Age) that her husband lost his own father to suicide as a teenager. So, there is possibly a barrier of unresolved grief and trauma that prevented him from reacting appropriately to his wife’s symptoms.

But presumably he noticed Melissa being ‘really down’ for those weeks. Did he attempt to get help for her? And if not then, what was stopping him when she expressed suicidal thoughts to him on that night? The fact that she claimed she wouldn’t act on those thoughts? Did he not consider the amount of mental pain one needs to be in just to have suicidal thoughts?

For everyone reading this: If anyone ever expresses suicidal thoughts to you, PLEASE ACT! Even if there is no option but an ambulance to the nearest hospital. And if the person experiencing suicidal thoughts tells you they won’t act on them, not only are they too unwell to make that assessment, they are also suffering intensely and need help!

Yes, our public mental health system needs a lot of improvement, and there are nowhere near enough public mother baby units available. But even if the ideal of a private psychiatric hospital with a mother baby unit, was not available or an option for Melissa and Lily, a public hospital might have given them a fighting chance.

Back for a moment to the journalists reporting on psychosis. They tend to give all the characters surrounding the person living the horror of psychosis a voice, even if some of those voices are irrelevant and add to the stigma psychosis is already steeped in.

In Melissa’s case that person is her baby’s great aunt. In The Age article, this great aunt doesn’t want to be named, but she does suck up more than her share of oxygen. She has publicly expressed that she thinks Melissa’s actions were ‘catastrophic’ and ‘cruel’. Catastrophic – absolutely. But ‘cruel’ implies the malicious intent of someone whose mental health is totally uncompromised. She used the words ‘Melissa’s actions’ but what she communicates is ‘Melissa is a cruel woman, and that is why she killed her baby.’

To that great aunt, I would say this:

If people like you didn’t perpetuate the stigma surrounding illnesses which feature psychosis by giving uninformed stigmatising quotes to journalists, then Lily’s father may have had some clue about what to do when presented with the symptoms of severe mental illness that were obvious in his poor wife for months before they led to such unbearable pain for everyone. If you want to blame something, blame this horrible illness, in the same way you might blame cancer for taking loved ones too soon.

News.com reports ‘The case has revealed just how quickly the 32-year-old’s life spiralled out of control after she developed severe major post-partum depression and psychosis following the birth of her daughter in April 2021.’

Melissa’s life didn’t spiral out of control quickly. She developed a life-threatening illness, the symptoms of which were either ignored or not acted on for months, until it was too late. Reporting it was quick, implies it was too quick to do anything about.

My postnatal psychosis set in by day 6 of first-time motherhood. By days 7 and 8 I was completely detached from reality, denying knowledge of my baby and my husband.

And when I was accurately diagnosed with postnatal psychosis in the safety of a mother baby unit in a private psychiatric hospital, my husband asked what he should have done if this had happened at home. This is what he was told:

‘Call an ambulance. Postnatal psychosis is a psychiatric emergency, but it is treatable.’

My greatest sympathy and compassion go out to Melissa. She was failed at so many points.

My memoir Abductions From My Beautiful Life was published last year and (among many other events) includes details of my experiences with Postnatal Psychosis. You can find an excerpt here: Book and it is available to buy online, including at Booktopia, Fishpond, and Amazon. If you are Brisbane based, you can also buy it at Avid Reader and Riverbend bookshops and Ruby Red Jewellery at 107 Romea St. The Gap.

If buying a new book is not in your budget, Abductions is also available to borrow from the Brisbane City Council Library Catalogue.

Other Thought Food posts that may interest you are:

My Sliding Doors Encounter With Our Public Mental Health System

Lifeline 13 11 14

What would you pack for a stay in a psychiatric hospital?

What would you pack for a stay in a psychiatric hospital?